Removing Exploitability: How I Think About Deckbuilding

05/08/2024

By now, I think I've proven my ability to brew constructed decks. Slogurk, Creativity, Spelunking, and RataBlade were team efforts and not solely my creations - but I had a big hand in all four.

That said, I'm not completely unwilling to play stock decks - in fact my first constructed tournament result was winning VML Season 8 (back when Fable was still legal) with a fairly stock Grixis Midrange list! I certainly have a bias towards brewing (partially because I find it fun and engaging), but I can recognize when a stock deck like Grixis is just the best deck in the format.

However, there are just many times when I think that you can just do a lot better than stock. cftsoc, who I've learned a lot from in testing with Sanctum, has a rule where they are pretty unwilling to register a stock deck for a tournament unless they think that they can gain meaningful advantage in the mirror - I'm a bit more willing to, I think, but not by much.

Personally, one of the reasons I avoid many stock decks is that many of them often have points of exploitable weakness. It's a concept I care a lot about, and something I actively attempt to build out of my decks.

So today I'm going to spend some time talking about exactly that: what exactly I mean by exploitability, how I try to attack meta decks based on their weaknesses, and how I try to remove exploitability from my own decks.

Defining "Exploitability"

To me, the concept of "exploitability" in deckbuilding is all about examining a deck by looking at its weak points, rather than looking at its strengths. It's not that hard to build a deck that wins when things are going well - it's much harder to build a deck that doesn't lose when things are going poorly.

In this sense, control decks tend to be some of the least exploitable decks out there - after all, one of the main tenets of a control deck is being able to have the right answer to whatever problem the opponent presents.

Midrange decks also tend not to have much exploitability, but approach that from the opposite angle - they generally try to present threats that are efficient enough to perform well in most situations.

Of course, not even control decks are unassailable on this front, as it's hard to truly cover everything. If I had a nickel for each format where UW control struggled against a land-based ramp/combo deck, I'd have at least two nickels right now: Temur Analyst in Standard and Lotus Field in Pioneer.

Both decks mainly deal in resources that UW control has a hard time interacting with (cards in hand and basic/hexproof lands in play), and overwhelm countermagic by assembling a large mana advantage.

Every deck will have its vulnerabilities - the point of focusing on those vulnerabilities is not to achieve the impossible of completely eliminating them, but instead to minimize them as much as possible.

All-In

One naive way to build constructed decks is to simply identify a synergy, and then go all-in on the synergy. You see this at its most extreme in certain combo decks, but this can happen in many other forms too.

Maybe you're building a cats typal deck, and so you make every single nonland card in your deck a cat. No removal spells, no card draw or filtering spells, just whatever effects you can find on creatures with the Cat type. The thought being: the whole point of building a cat typal deck is that you have payoffs that scale based on the number of cats you control, so surely you should maximize on that in order to make your deck better, right?

Or for another example: maybe you're building, say, an Analyst ramp deck in Standard.

Aftermath Analyst as a card is pretty strong when you have a bunch of lands in the graveyard, so it's pretty natural to want to put self-mill cards like Fallaji Archaeologist in your deck to make Analyst better. The early builds of Temur Analyst did this exactly.

The problem is that often going all-in on your main plan leaves you open to being weaker when you aren't able to enact that main plan. If you make your entire deck cats, your cards are likely going to be quite underpowered when your opponent removes your typal payoffs. If you stuff your Analyst decks with dedicated self-mill, you might struggle if you never draw Analyst, or if your opponent has effective ways of interacting with it like

Tishana's Tidebinder.The truth is, while it is important to make sure that your deck actually does something powerful when functioning at full capacity; it's arguably even more important to figure out how to mitigate what happens when it's not functioning well.

Of course, sometimes it's still worth it to go all-in. Some synergies even require it - the epitome of this is probably Oops! All Spells, but I'd also point at decks using the literal Affinity mechanic. But you should still be very careful to consider the tradeoffs.

It's very easy to get tricked by wanting to maximize the ceiling of your deck, when the ceiling actually doesn't matter much. There are many situations where winning even more won't do much, and it's a lot more effective to focus on making your deck more resilient to situations where it doesn't play well.

Amusingly, one of the most common places I see this happen is with decks made by content creators - and for very good reason! This is a good way to build a deck made for content, as maximizing for a specific thing often makes the ceiling a lot more fun to watch. But good content does not equate good strategy.

Interaction Suites

Another subtler and more specific way that decks can often be exploited is through having limited interaction suites.

A classic example of this are midrange decks in Standard right now that play only

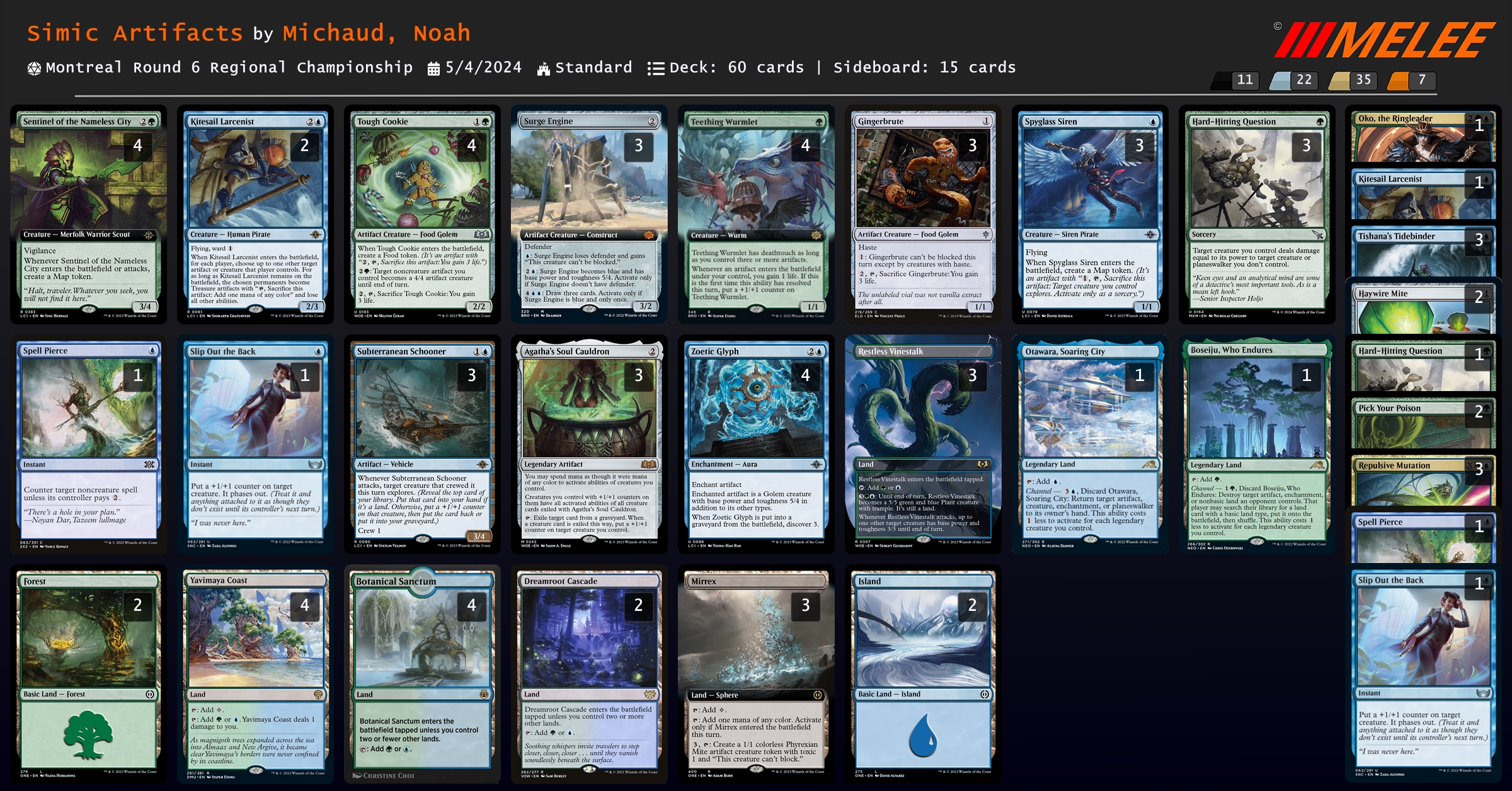

Cut Down and Go for the Throat for their removal. Both of those are generally quite excellent in the meta, and are very good against the majority of decks - but playing no other removal spells can leave you weirdly weak to mid-to-large-sized artifacts like Thran Spider or Phyrexian Fleshgorger.In fact, at the recent Montreal Regional Championship, there was a Simic Cookies deck that top 8'd, doing well largely by exploiting the fact that many of its threats dodge the most popular removal spell in the format!

Resiliency to Hate

Finally, there's also a kind of exploitability related to folding to specific kinds of targeted hate.

If your deck relies on graveyard synergies, you should consider how it does against sideboarded graveyard hate, and whether you need to take steps to be able to deal with with such hate. If your deck relies on tapping out for expensive spells, consider how it fares against countermagic.

Part 2, An Example: Exploiting the 2023 Standard Meta

In the summer of 2023, I was preparing for VML Champs. This was a small-field, high-stakes tournament - 24 competitors, with the top 2 earning PT invites. The formats were LTR draft and Standard.

Standard was in a weird spot at that point. Fable, Bankbuster, and Invoke Despair had been banned almost 3 months ago in May; but there hadn't really been a big tournament since then - Arena Championship 3 was the only real Standard tournament around then, and it was before the ban. So not many people had any incentive to play.

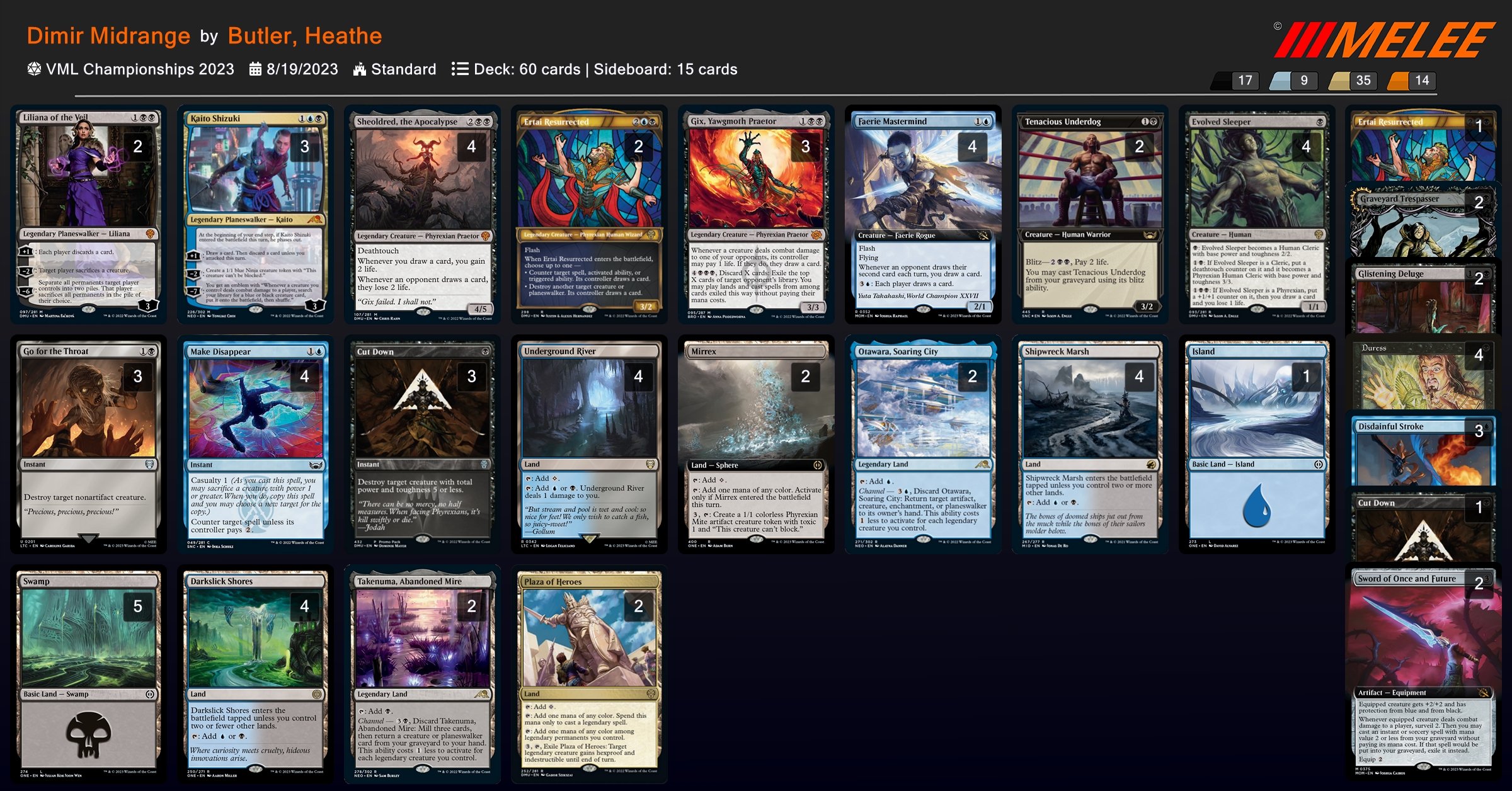

The most popular deck at that point was definitely Dimir Midrange - Esper had not yet been refined, though Sky and Jesse brought an early version to the tournament.

Domain still existed as another part of the format - but it didn't have access to

Cavern of Souls. So Dimir was able to exploit that weakness by leveraging Make Disappear and other countermagic to become the dominant deck, while Domain pushed out a lot of non-blue decks.So, going into this format, my goal was to try to find a deck that could fit between those two extremes. I wanted to be able to either contend with Domain's lategame, or exploit some of its clunkiness by being able to fit in countermagic myself; and I wanted to be resilient to both Make Disappear and removal out of Dimir while playing well against its underpowered threats.

My first thought was actually Chandra turns combo - a spell-based deck built around

Chandra, Hope's Beacon, Light Up the Night, and Alchemist's Gambit that could trivially kill Domain and made creature removal entirely irrelevant. However, I discard that idea pretty quickly, as Chandra itself was extremely weak to countermagic as a 6 mana card. So I looked for cheaper options.And that's how I found

Slogurk, the Overslime. I'd played the 4-color legends deck with Raffine back when it came out of Japan and put up results at a Canadian RC, so I was familiar with just how strong the Slogurk lategame could be; and as a 3 mana card, I thought that Slogurk would be the perfect lategame engine to try to push through Make Disappears.Of course, the deck I ended up on wasn't anywhere near the final form of the Slogurk that we have now. But I think it was a decent attempt at getting a leg up on the competition, which sadly did not have much of a chance to shine due to my 0-3 draft.

Part 3, Another Example: Removing Exploitability from Analyst

Temur Analyst

The evolution of Temur Analyst in Standard is an excellent example of how to remove exploitability from a deck. You saw one of the earliest versions above; here's a much more up-to-date list, the one that brought Sean Goddard to top 8 at the PT:

The core package of cards have stayed the same (Analyst, Nissa, Virtue, Rage, Deluge, Explosion), but a lot has changed around it to make the deck more flexible and resilient to hate.

First of all, the deck now features more interaction, in the form of 3 copies of

Fires of Victory. This allows the deck to be a lot more able to play from behind, as it can slow the opponent down a lot more consistently. The extra removal also allows the deck to more consistently deal with problematic disruptive creatures - most relevantly Deep-Cavern Bat and Elesh Norn, Mother of Machines.We also see 3 copies of

Spelunking being adopted as a different angle of ramp that augments the main plan. The card can serve as a third accelerant to make your Nissas and Analysts even better, but also serves to just provide more ways to get towards your big mana plays when you can't manage to get value from Nissa or Analyst.And finally, we see a nice set of sideboard tools that let the deck play a scrappier game postboard, when the opponent is more likely to have targeted hate like Rest in Peace.

Titan of Industry, Bonny Pall, Clearcutter, and Doppelgang all shine here as large threats that you can ramp to that don't require the graveyard to function and also don't require you to have actually put all your lands on the battlefield to work.All of these choices point to a very well-tuned list. Sean clearly recognized that you didn't really need to augment your main gameplan much at all, since it's already powerful enough to win easily when it works. Instead he dedicated slots both maindeck and sideboard to patch up the vulnerabilities the deck had, and ensure that even when his deck wasn't able to enact its main gameplan, it could still make reasonable and productive plays.

Personally, I still am interested in going even further in patching up Analyst's weaknesses - I'm specifically interested in whether you can fit black mana for better removal and/or sideboard Duress - but that might be a bridge too far, and more importantly is probably a topic for another time.

Conclusion

Exploitability is probably one of the biggest things I think about in brewing and deckbuilding. It's why I'm loathe to register any all-in combo deck, and why I often stay away from stock decks - I just think you can do better.

It's just so easy to focus on the wrong things, especially when you have a strong explicit synergy to build around. But unfortunately, in Magic you don't get more points for winning more.

#FreePalestine | Consider donating to UNWRA or PCRF, supporting protesters locally, and educating yourself.