Drafting with Upside

12/22/2023

You've probably heard of the phrase "drafting the hard way". It's a term coined by Ben Stark, one that's served as conventional limited wisdom for quite a long time.

The concept is pretty simple: "drafting the hard way" is another way to say "don't just draft the easy way", where "the easy way" is being overly reliant on sticking to your early picks. In his article, Stark talks a lot about figuring out what the open lane is - paying attention to which colors are open, and being willing to completely jump ship from your starting picks for a better seat.

However, if you're tuned into modern limited discourse, you might also have heard that, while it is still a useful skill to have, "drafting the hard way" has slowly been falling out of favor.

This isn't to say that you should just always force your first picks. It's still important to recognize when and how to pivot! But with modern limited design, it has become a lot less common to do a complete 180. What changed?

Part 1: Modern Limited Design

For quite a while now, limited sets have had quite a large density of playable cards. I'm not sure exactly when this started being true - I think it was a gradual change, starting sometime around Guilds of Ravnica or War of the Spark - but these days it's actually pretty hard to end up short on playables. And naturally, if it's easier to find playables, then you're more likely to be able to make a less open color work.

Khans is actually quite an interesting comparison point here, as an old set that has recently been ported to Arena. With 17lands data, we can do a bit of comparison between it and more recent sets like LCI and WOE:

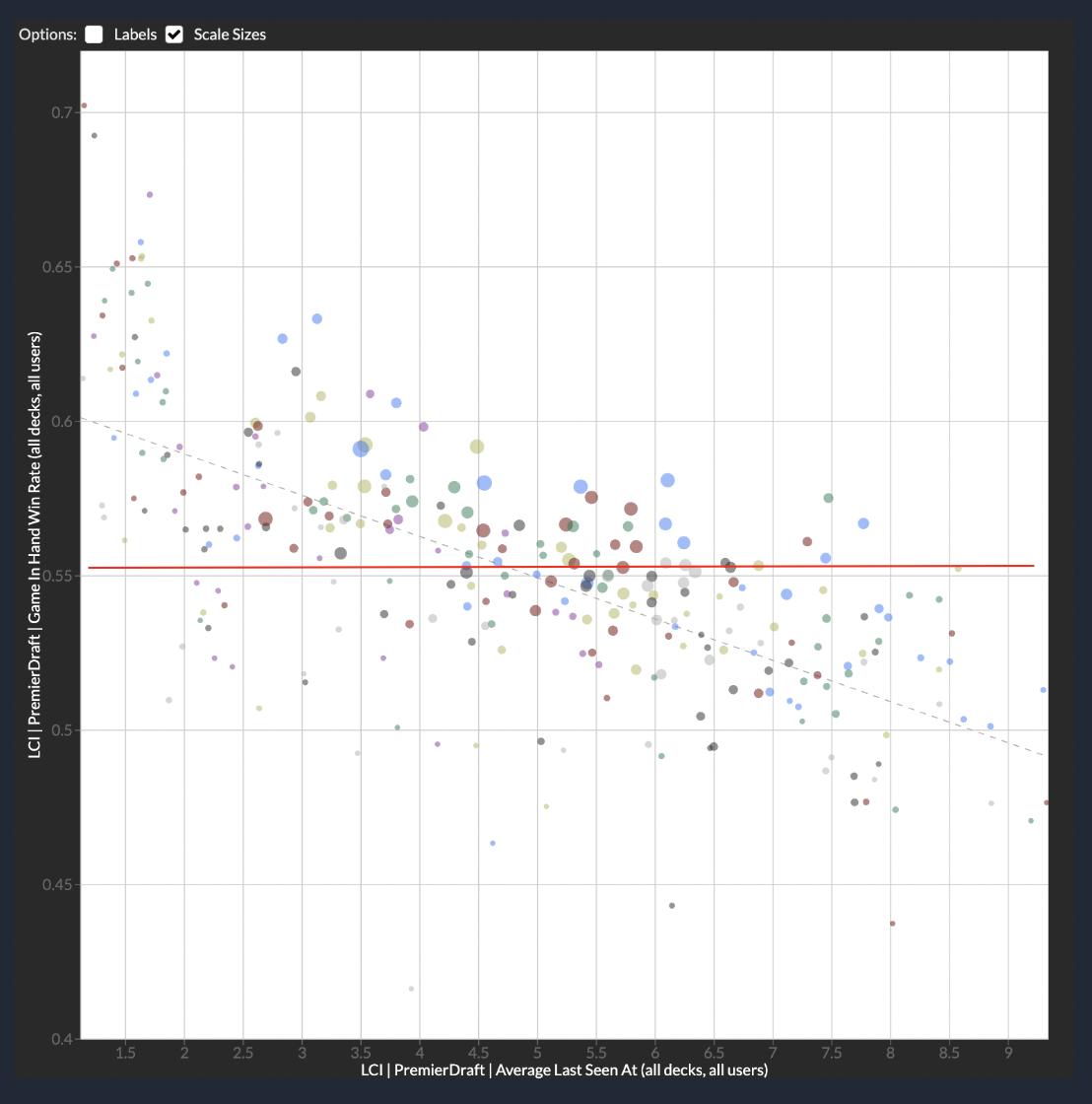

a chart from 17lands showing LCI GIH WR vs ALSA; the red line represents format average winrate (55.3%)

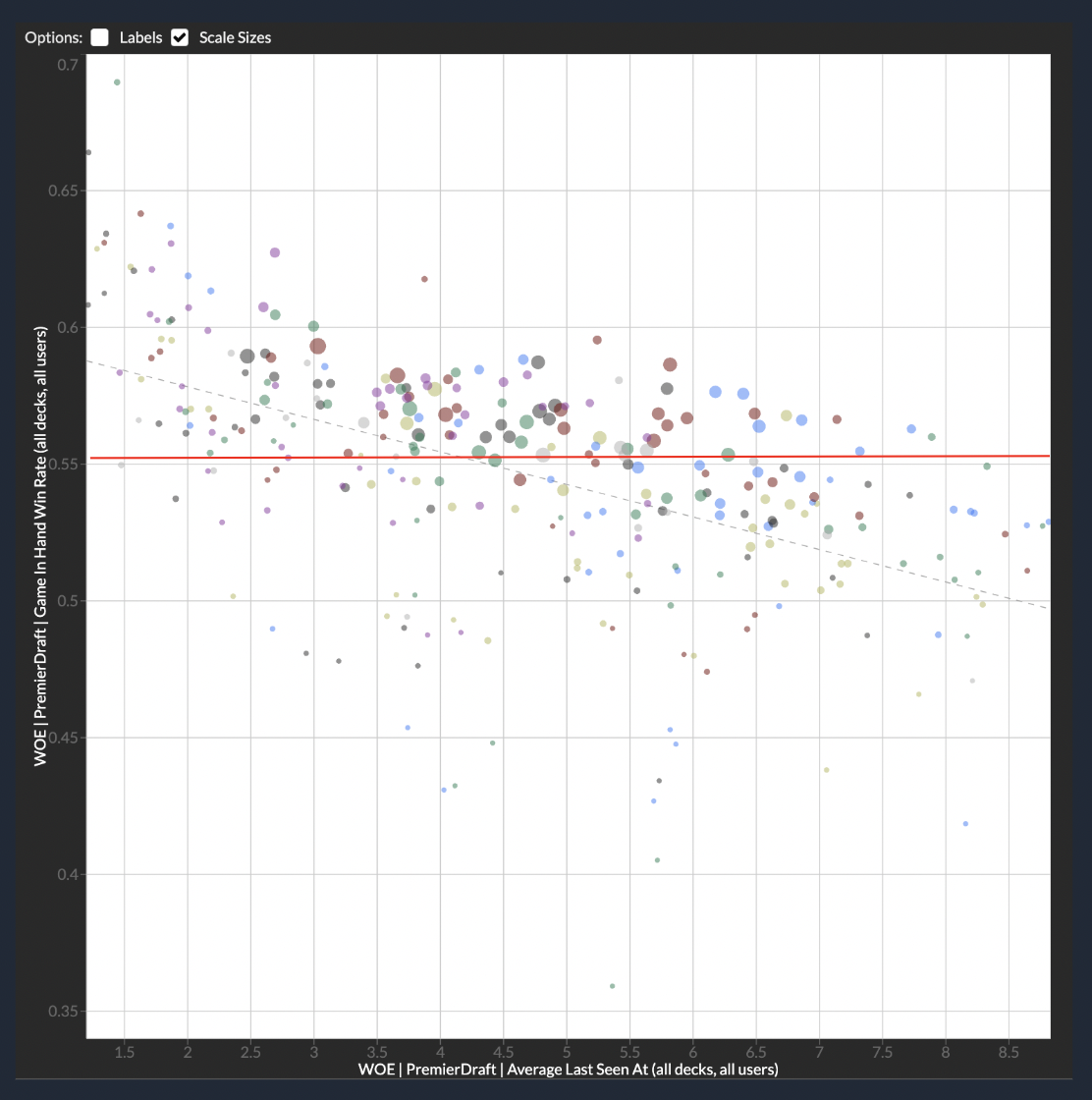

the same chart for WOE (55.2% format winrate)

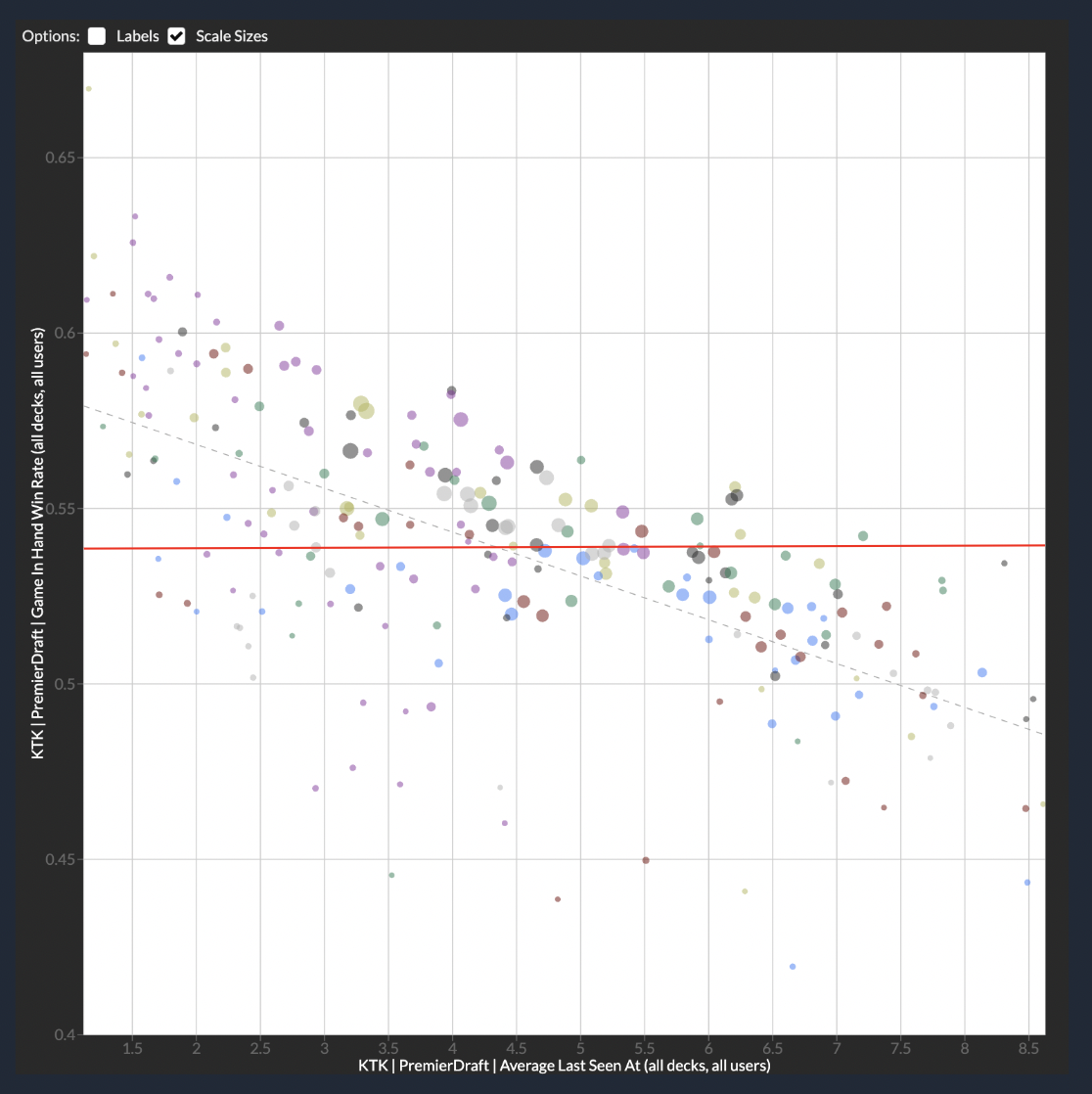

and finally, the same chart for KTK (54.0% format winrate); note how, for the more recent two sets, solidly more than half of the cards seem to be above the line, and for KTK it's more like a 50/50

It turns out that, while they all have a similar number of total cards, WOE and LCI have 152 and 146 cards above format average winrate; meanwhile KTK only has 109. And among commons, WOE and LCI have 43 and 37; KTK only has 31.

Obviously, "above average winrate" isn't exactly the right metric for whether a card is good or filler. But this still shows a pretty stark difference - in KTK, only about 40% of the cards have above average winrate. This suggests that, if you're not in an open seat you're almost guaranteed to have to play mediocre cards (40% of 45 cards drafted is 18).

Compare that to modern sets, like WOE and LCI here. Approximately 60% of cards in the set have above average winrate - so out of 45 cards drafted that's 27 cards, which is notably more than 23! And again, this napkin math isn't quite accurate to how drafting works, but it certainly points at a very real phenomenon. Compared to a set like KTK, you're just so much more likely to be flush with good cards at the end of the draft, and likely to still see good cards going 2-3 picks later.

So, how should this change how we draft?

Part 2: The Upside

In some senses, "drafting the hard way" is a pessimistic philosophy, all about avoiding disaster. The main focus is on not trainwrecking - Stark posits that "drafting the easy way" is high variance, leading to some 3-0 spikes but also a fair share of 0-3s and 1-2s; and on the flip side, "drafting the hard way" lets you consistently have a good deck, with maybe fewer 3-0s, but more expected wins overall.

But as discussed above, nowadays "disaster" is a lot less common, and a lot less disastrous. I can't remember the last time I truly felt that I would trainwreck if I'd just hard forced a pair of colors - at worst, I'd just have a mediocre deck, but still a playable one. If anything, my trainwrecks have been when I get a bit too ambitious, speculating on a bit too many different lanes with no payoff.

So, if a pessimistic view of drafting no longer suits modern limited design, then I would propose an optimistic one: something I like to call "drafting with upside".

The idea is simple; the most important question to ask yourself when drafting a card is:

"What is the upside of this card?"

How does it contribute to your final deck? After all, the end goal of draft is ultimately to build the best deck at the end. If you're not taking something that will improve your deck, then you're just wasting a pick. Then, naturally, the question of what to pick becomes a question of which card will most contribute to your final deck.

Part 3: But what does my deck look like?

Of course, there's a lot of hidden complexity buried in the question "how does this card contribute to my final deck?" After all, you don't know for sure what your deck will look like until the end of the draft!

However, while you might not know exactly what it will look like, you can certainly make some educated guesses. And as the draft goes on, those guesses will get more accurate.

For example, at the beginning of the draft, you have no idea what your deck will look like - it could be literally anything. But once you've taken a strong bomb rare, you can probably guess that your final deck is fairly likely to contain that rare. And as you take more strong cards of the same color, you can start to expect that your deck will be that color.

Multiplicity

So far, it sounds kind of like I'm just describing forcing a deck - and in some sense, you could apply this to forcing. That would look like fixing a complete image of your final deck at the start of the draft, and not deviating from there.

But the key is: you can and should be theorizing several different decks as you go, each with some probability of being what you land on. Forcing is what happens when you decide early that you're going to be 100% to end up in a certain deck - when in reality it should take quite a while before you're that certain.

[Expected Upside] = [Chance of playing it] * [Upside if played]

The above equation is a bit silly, as card evaluation is not an exact science. However, it illustrates an important point: a card's value is not just tied to its upside if you end up putting it in your deck, but also how likely it is for you to put it in your deck.

A bomb that makes your deck 10% of the time is likely worse than a solid common that makes your deck 90% of the time. Is the same true if the bomb is 30% to make it? How about 50%? It's impossible to say where the exact cutoff might be, but it's still important to keep in mind that this is a significant factor.

And, of course, this ties into the concept of theorizing multiple decks - if you're deep into blue in the middle of pack 1, you can think of your final deck as something like 80% to be blue and 30% to be each of the other four colors. So then, a decent blue card might be a better pick than a slightly better non-blue card, as it's more likely to make your deck. But if the power difference is significant, then maybe the other card provides more expected value.

Part 4: Different Kinds of Upside

There are, of course, a lot of different factors that go into figuring out what the "upside" of a card is.

The most basic is raw card strength: some cards are just better than others. Knowing which cards are generally stronger in a format and which cards are weaker is a matter of card evaluation and format knowledge.

Then there's synergy; this can be thought of as a modifier to raw card strength. Does the card in question perform notably better or worse than usual in my deck? This includes both broad synergy like being more aggressive or controlling, and specific synergies like "I care about artifacts" or "I care about descend". For some cards this will matter a lot; for others, very little.

And finally, there's even more deck-specific questions: questions like "do I need more 2-drops?" or "do I need more interaction?" or "do I need more ways to push damage?" Always remember that you're drafting a deck, not just cards - recognize when your deck has a hole that needs addressing more than it needs generic raw power.

24th card = 0 upside

Honestly, one of the most important takeaways from this framework is that you shouldn't take cards that have close to zero upside.

Modern limited sets tend to have a higher density of playable cards, yes; but there are still

quite a few mediocre cards, and some unplayable ones too.It's fairly obvious that you shouldn't take unplayable cards - most people will recognize a card is unplayable and avoid it. But you should also avoid taking 24th cards - that is, cards that aren't unplayable, but are mediocre enough that they will likely end up being left in the sideboard unless you're really short on playables.

The upside to taking these cards is just so minimal - maybe they fill out your deck if you're really struggling for playables, but again, that just doesn't happen that much in modern limited. If there's nothing better, sure you can go ahead and take a 24th card, but you should also consider speculating on another color or a sideboard card instead.

Notably, there are a couple classes of cards that are never really "24th cards": lands, and sideboard cards.

Lands are very nice because they will basically always make your deck - so they always have a guaranteed, if small, amount of upside. And if you're at a point where you're pretty guaranteed to have enough playables, this can be significantly more upside than upgrading your 23rd card.

Sideboard cards are weirder. They don't provide value all the time, but occasionally they will more than make up for that. For these cards, instead of thinking about how likely they are to make your deck, you should think about how likely they are to be sided in.

Conclusion

This has been somewhat less concrete of an article, but then again, draft theory is never particularly concrete.

In the end, "drafting with upside" comes down to four steps:

- 1. Think of what your deck is likely to look like at the end of the draft.

- 2. Consider multiple different possibilities for the above, and think of how likely each possibility is.

- 3. Figure out how each card fits into each deck; how does each of them improve your possible decks?

- 4. Take cards that have high upside this way, and not ones with low upside.

#FreePalestine | Consider donating to UNWRA or PCRF, supporting protesters locally, and educating yourself.